Jurisdiction: Country Risk and some personal observations from Canada, Australia, Central Asia & Europe

More episodes

Transcript

When it comes to jurisdiction, many people have strong opinions about which countries work and which countries don't. But as in every aspect of natural resources and the mining sector, there's a risk and reward balance that needs to be understood and then put into perspective before one makes one's final decision about jurisdiction. Clearly, the more unstable a country, the less easy it is

it is to get debt funding for example, or there may be heightened security risks, let alone equity funding. Equally, there may be opportunities in that country which are not available in a more developed country where there's greater stability and a lower cost of capital. So it's necessary to balance the opportunities and the challenges of the country in which you're operating or the location of your project. A few years ago

I very much enjoyed a panel session in a conference where the CEOs of a number of companies operating in Africa were invited to present on managing country risk. The speakers included the CEO of Banro operating in the DRC, the CEO of Sentamin operating in Egypt, the CEO of Kola Africa operating in South Africa and I think the CEO of Base Resources operating in Kenya. The presentations about the DRC, Egypt, South Africa and Kenya were

all memorable by virtue of the fact that all of the CEOs were entirely comfortable with the risks that they were facing in country. Each of them argued cogently and in completely good faith that their own countries were fine and that they wouldn't invest anywhere else. Ha! It made me realise that confirmation bias is a powerful thing and that objectivity is absolutely critical. Clearly, what each of these CEOs had experienced is that the better one gets to know a country, the more one can accommodate how to work it, where the obstacles are and how to work around them.

They were dealing with the risk because it was what they had to do, which is very different to the options open to an investor when looking at where to put their money. For the investor, with a choice of investing in any geography, it's worth stripping emotion out of the decisions and going back to check the numbers on a purely analytical level. While it may be stating the obvious, investment opportunities where companies have assets in developing economies or frontier markets are accompanied by higher risk because of the geopolitical and macroeconomic risk factors that need to be considered.

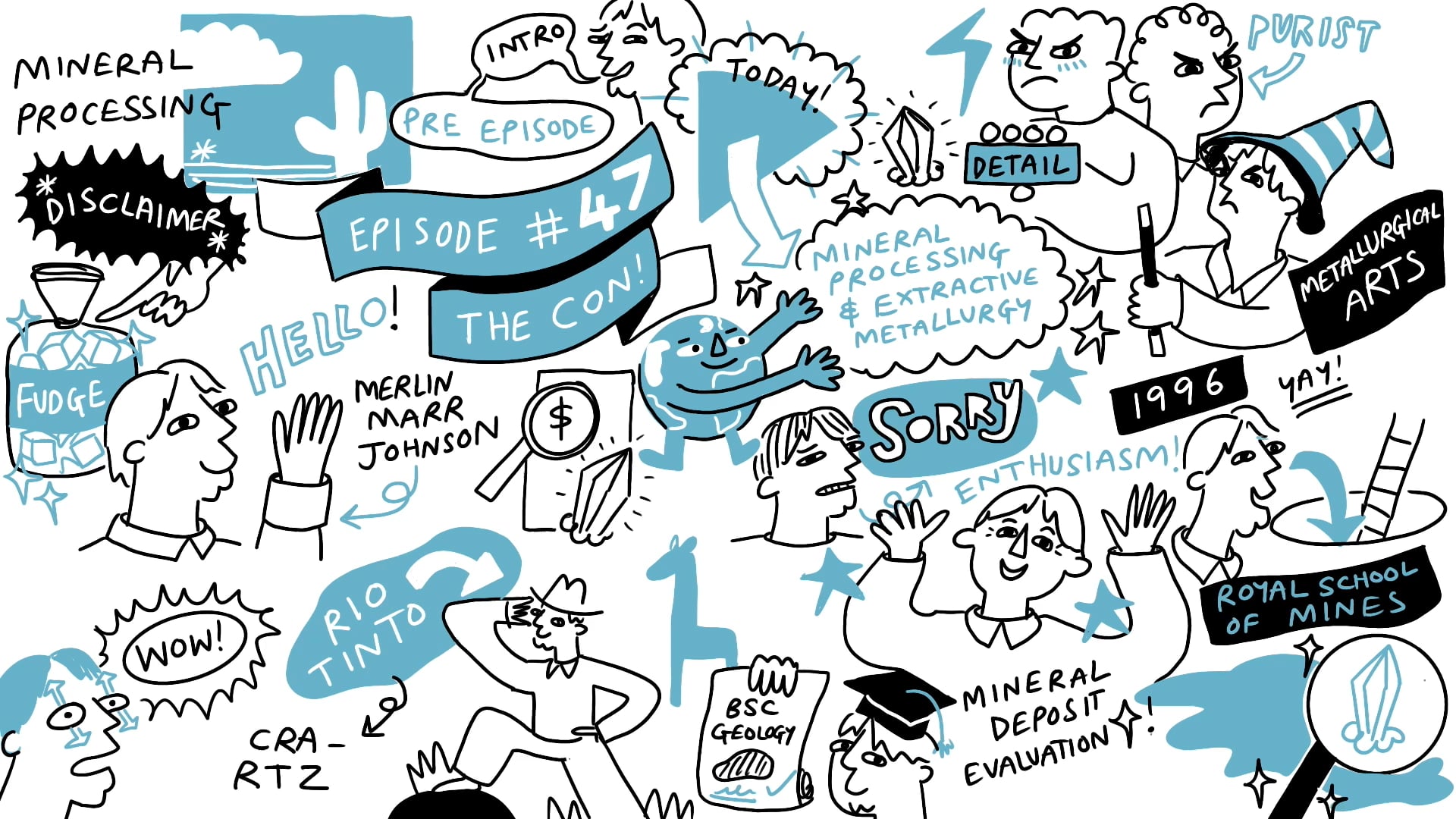

Merlin Marr-Johnson (02:17.602)

To get a handle on what that means in terms of numbers, have a look online for data on Country Risk Premier or Country Risk Ratings or Moody's Ratings or have a look at the work done by Professor Aswath Damodaran at NYU Stern. He compiles data on risk premier globally. All of this data gives you a completely objective set of numbers with which to frame your investment thesis and they are key reminders that economic risk can be quantified.

and viewed statistically through large datasets. And the information is available should you want to filter your decision-making process accordingly. I think it's really interesting, you know, I've had a look at some countries myself and I thought, oh, goodness, okay, that's how it's being measured in the markets. On a more personal level, here are some of my own

observations. I've worked in many of the countries in South America, Africa, Europe and Central Asia. I haven't spent much time in Oceania, Australia and Southeast Asia, nor in North America or Central America.

What I do find is that in every country one works in there are obstacles and there are opportunities. At a headline level it's relatively easy to choose your country based on commodity. If you're looking for gold for example you might consider the gold belts wherever they are. I don't know, Lappland in northern Finland or West Africa or the Greenstone belts of Zimbabwe, Canada or Australia. If you're looking for copper you might want to go to Zambia or Botswana, Chile, Peru or to Ecuador and obviously...

If you're looking for uranium, you might choose Namibia or Niger, Kazakhstan, Australia or Canada. And frankly, if you're looking for anything high grade, pick a commodity, any commodity, you might want to go to the DRC. However, each of these places come with particular challenges, and the closer you look, the harder everything becomes. And it's not just the high risk countries that are difficult, but actually the developed countries as well. Canada, Australia, or Nevada in the US for that matter. So, Canada and Australia.

In Canada or Australia, there's vast competition for ground and assets, and they are both extremely mature exploration environments. On top of that, you've got the first nations populations and very stringent permitting protocols to get your mind built. There's a lot of scrutiny of your work practices and you have to do everything in an extremely ordered manner to make progress. Well, having said that in the age of mobile phone cameras, there's a lot of scrutiny wherever you work, but there's definitely scrutiny in the developed countries. In addition,

Merlin Marr-Johnson (04:37.866)

The environmental requirements to get a mine permitted are such that it can take years, if not decades, to get all of the licenses issued. Stephen Roman, who runs Global Atomic Corporation, is the first to say that it takes so long to get anything done in Canada. It took Stephen 10 years to get the Sugar Zone gold mine permitted in Northern Ontario. He'll also tell you that it took Denison Mines about 30 years to get the last uranium mill permitted. His view...

is that it simply takes far too long to get things done in Canada. And not only are the timelines extended, but the competition for assets is so great that it's very hard to find something good, which is just sticking out of the ground. Or if it is sticking out of the ground, it's miles away from anywhere. Remember that Canada is a big country with harsh winters and a remote project can create real infrastructure and operating challenges that negatively impact the economics. And there's a similar situation in Australia.

While Australia is a well established mining country and people are willing to invest into Australia again, it's been massively explored. All of the easy stuff has been found. You've got timeline challenges to get your permits issued. And it's not actually that easy to bring a project into production. What of course is worth noting is that because Australia and Canada see a lot of the exploration investment dollars, there's a lot of new data being produced which favours discovery.

turning over the ground, taking samples, drilling holes. At some levels, discovery is a numbers game where the more good targets that are tested, the greater chance of making a discovery in a country. So it's no surprise to see that there are good deposits still being found in Australia and Canada because that's where the work is still going on. Nevertheless, over time, people and companies are willing to take risks in new countries. They go where the assets are. Rio Tinto, for example, went into Chile at a time when Pinochet was still rounding up people and shooting them in football stadia.

They went in with BHP on Escondida. Big companies are willing to take long-term risks when the asset is worth it, and that really is the key aspect about jurisdiction, the balance between opportunity and challenge. What this means is that everybody will look at the opportunities of what asset is in front of them, and they'll take it from there. To give a few examples of the opportunity challenge issue.

Merlin Marr-Johnson (06:38.034)

Adolf Lundin who was the Swedish magnate who established the Lundin family of companies, the father to Lucas and Ian who run the oil and mining business now. Well Adolf was a buccaneering Swedish entrepreneur who was somewhat famous for taking political risk and investment decisions in countries where he felt the asset was worth it. This was in the bad old days when one could pay bribes almost openly. You could call them commissions or introductory fees in those days.

Famously, he was trying to get a concession for an oil deal in Qatar and he had been camped at the door of the Ministry for about two to three weeks and he couldn't get a meeting Eventually he got a meeting but no deal and he said you know what? I'm an expert weather forecaster I'll bet you a million dollars that it'll rain tomorrow in Qatar. The sheikh accepted the bet Adolf Lundin lost the bet. He paid up the million dollars and guess what? Next day he got his concessions. It's that

crazy buccaneering stuff where he was prepared to take a leap on the jurisdiction perspective in a country where you can bribe officials to get the asset you want. And not that I'm condoning that kind of behaviour, mind. Goodness me, no. Anyway, moving on to some of my personal thoughts about various geographies around the world. These are just my personal observations, nothing more and nothing less, and will probably demonstrate my ignorance rather than my knowledge. But for what it's worth, here we go. Central Asia.

Western investors have a relatively healthy allergic reaction to Central Asia. Generally people say they won't work in the stands because they're just too difficult. I would say that working there is difficult but it's not impossible and there are many Soviet attitudes that one needs to overcome. There's also a cultural difference which is actually much greater than just the language barrier. But even if you translate the language you can't actually or you still can't really understand the culture. These are Soviet attitudes which are deeply entrenched.

and it takes a long time to understand it and trust is a big issue. But if you spend time in the country, you can get things done and you can get your rewards there. For example, Kazakhstan is definitely workable. Yes, there are some big forces moving around at the

governmental level, which are challenging to navigate. But if you keep your head down, stick to the protocols and the law, you can have a healthy function in corporate life in Kazakhstan, as demonstrated by Central Asian Metals with their tailings project. Kyrgyzstan is a much harder place to work.

Merlin Marr-Johnson (08:49.298)

The country has been independent for 30 years and government has been extremely unstable. Centera have had a nightmare trying to work at Kum Tor over the years despite good production levels and it culminated unfortunately in the seizure of the mine by the Kyrgyz authorities in May of this year and just last week recent images of about 40 metres of water in the bottom of the pit raise operating and perhaps more importantly safety concerns about how it's being run at the moment. Another fabulous gold deposit, Jurui, has had a checkered ownership history and is now

so completely under Russian influence that Vladimir Putin himself oversaw, via video link, the opening of the plant in March. In short, Kyrgyzstan is off limits at the moment. Uzbekistan, on the other hand, is gradually opening up. Corporation tax is down at 7.5% and there are properties being auctioned on a monthly basis. The government has advertised that they're looking to liberalise the economy and base it on a mining growth potential and opportunity. There's great geological potential but so far access to real data sets remains restricted. Let's see whether that opens up.

Tajikistan not yet, Turkmenistan forget it. In summary, Central Asia, the door is almost completely shut, but it's not completely shut. You can work in Kazakhstan and you will in the future likely be able to work in Uzbekistan. Perhaps now is the time to be looking there? Question mark. Moving west to the Caucasus, Armenia used to be workable. The Armenian diaspora meant that the country was very interested in global affairs. It was the West and leaning. And it was a nation that depended on migration of money, people and ideas. Now, of course, that's all changed with the war. Azerbaijan was...

has always been incredibly difficult. I've spent a lot of time looking at Uzbekistan and Georgia was also too hard. And so if you look at all three of those, generally the Caucasus is too difficult. The Balkans however is completely different. Kettle of Fish were firmly in Europe by this stage. Adriatic metals have had great success in former Yugoslavia. It's

Former Yugoslavia, I would say it's slow, even though Adriatic Metals is actually cutting through the red tape excellently. There is great geology and manageable mining politics in the wider region as far south as Greece. Greece, unfortunately, is not workable. They've got great geology, but they've pretty much decided against mining. It's not the only country in Europe as well. Many European countries are slow or not in favor of mining. Thus, it's hard for resource companies to actually make any real progress there, such as in Italy or in Spain. It's hard, yacka.

Merlin Marr-Johnson (11:03.894)

as the Aussies would say. Italy, mm, AltaZinc are making progress on that zinc project, which is good, but generally it's quite hard. Spain, again, a very mixed bag. Permitting is so hard, but in some places you can work, and of course there are some mines down in the South,

well, not just down in the South, but there are some mines operating in Spain. Romania, so many have tried and failed, and France is particularly crazy. For example, I can take you to a district with 4 million ounces of gold potential, and yet there's no support for it.

at the community level or at the governmental level. Try getting an exploration permit or access to drill in France. It's almost impossible. And yet there's rural flight, there's a jobs crisis. The logic of having a homegrown industry is staring them in the face and yet they are unwilling to consider it. It's one of those funny things. Perhaps it's a mentality problem. I mean the motorcar for example has evolved so much over the last 40 years. If you see what it does, which is move people from A to B, it still does it.

but in a completely different way with completely different safety and emission standards very much like mining industry in the old days they were dirty, unsafe and polluting now they can be neat and almost run remotely with very low emissions and very low impact and good local job opportunities yet there are so many European countries which are pretty slow to wake up to it but, you know, rant over there are a few notable exceptions to the European gloom the Republic of Ireland for example has some fantastic infrastructure

and a superb body of scientists and regulators that really understand the potential of a resource industry. iCRAG is a government-supported geosciences centre hosted by University College Dublin. It's amazing. The Republic of Ireland government is so supportive and the country is such a good place to operate. Mind you, the geology is difficult and yields its riches very slowly. But zinc and gold, it's there. Scotland is something of a surprise in recent years. It's open to investment now and it's surprisingly prospective.

although it hasn't got a great track record of delivering large resources. We live in hope. And the great expectation is that Scandinavia will become a haven for investors in the mining sector. At one level, slightly more cautious about that, remind people that Scandinavia is largely run by the reindeer. So it's reindeers first, people second and mines third. Sweden as a mining nation is a surprisingly difficult place to get mining projects up and running. The Swedish government is run by coalitions.

Merlin Marr-Johnson (13:24.246)

consensus and committee and therefore no decisions are made. People are unwilling to say we're going to develop human capital or a mine here because it might impact a reindeer, for example. I'm being facetious, but it seems that no one is prepared to make decisions about the long-term development of the country. And despite the fact that Sweden has lots of mines, it has very weak institutions filled with people who don't necessarily understand the mining sector. And therefore there's a lack of trust even between the regulator and the operating mines. Finland has great potential. It has an extremely onerous

permitting framework, a situation which is complicated and has long timelines, but you can get things permitted despite those long timelines. The point is that the geological rewards are evident because the deposits found in the central Lapland Gold Belt in northern Finland are sufficiently attractive to warrant the investment required in terms of time and effort to get access to those projects.

is Agnico Eagles single largest resource base, in terms of the ounces contained. And other companies are going great guns in the region. Now there are honorable mentions to Orion Resources and Mawson Resources, but Rupert Resources are really leading the exploration charge in terms of new ounces being discovered in the central Lapland Gold Belt. Superb discoveries, superb work. Agnico will I'm sure want to consolidate its position in the region, yeah.

Finland's great.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)